How to Make a Paramount Record (1930) from

kellianderson on

Vimeo.

I've written about Jack White (ad nauseum, some might feel), I've written about Third Man Records, I've written about blues music. But it occurred to me that I've not yet written about The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records, which is an oddly glaring omission as it's the pinnacle of those three things which have become such a focus in my life, my three primary addictions of recent years.

Addiction is a perverse and contrary thing. There's almost a stereotype in the picture of an addict doing things that make absolutely no sense in order to fulfill their need, especially when the need itself makes questionable sense. My own addiction recently compelled me yet again to travel hundreds of miles to see Jack White. But this wasn't for a show by him, though there was music. No, instead of being surrounded by a band, on this night at Battell Chapel on the campus of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, Jack was surrounded by a panel consisting of a Yale professor of African-American studies, two music writers, a female blues singer, and a fellow record label owner. This group was in New Haven for the follow-up to an event last year at the New York Public Library, which I also attended, discussing The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records, Volumes One and Two, released by Revenant Records and Third Man Records.

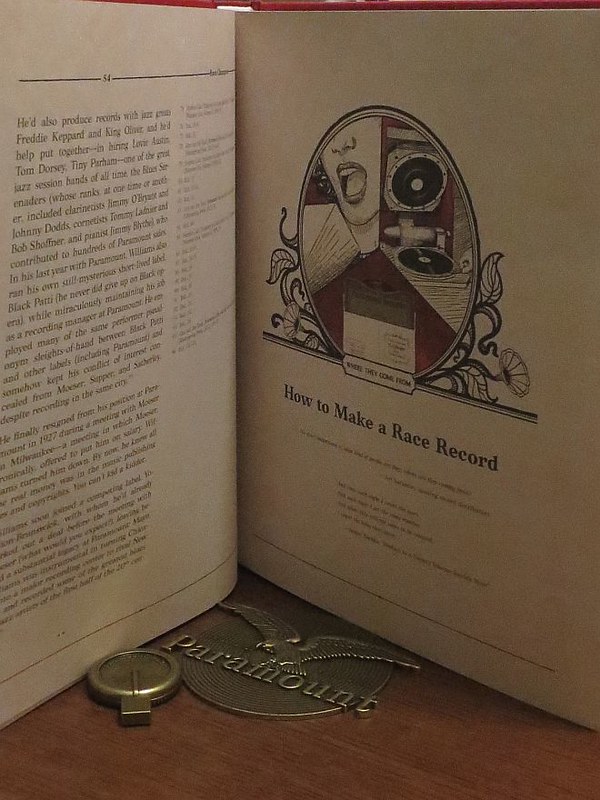

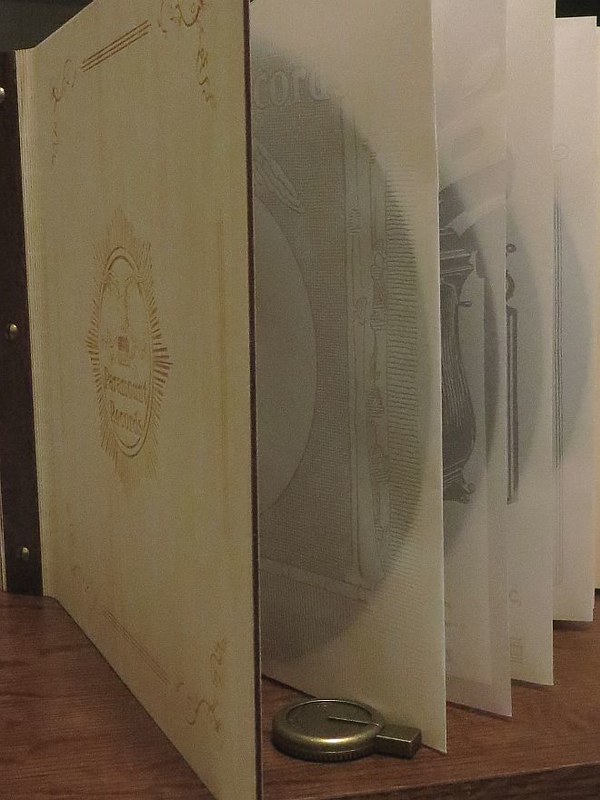

But it wasn't only Jack that motivated me to make the drive from D.C. to Connecticut. There was also my covetousness of these Cabinets of Wonder and everything they represent. When Volume One was released at the end of October of last year, I already had plans to be in Nashville that very week. So the very first day it became available, I walked into Third Man Records, drooled over the components of the set for a while, debated about the physical mass of it and the gigantic carton it was packaged in and how the heck I was going to get it home, then said "Damn the torpedoes" and plunked down my credit card. Two days later, I bought a 50 foot roll of bubble-wrap, a large roll of tape, and spent an evening of my vacation removing the two large books from the cabinet (they went into my suitcase) and then painstakingly wrapping it, with the records enclosed, in almost the entire roll of bubble so that I could carry it home with me on the airplane. Heading home from Nashville, I thought my arms were going to stretch by a good couple of inches from the weight of the solid oak box as I hauled it through the airport. Had two moments of panic, the first at the security gate when the screener asked what was inside all that bubble and warned that they might have to un-wrap it if they couldn't get a clear view in the x-ray machine. The second was when I got to the plane and was informed by the flight attendant that it would not fit into the overhead bins of the tiny three-seat-across plane. She asked what was in it and then wondered why I hadn't just shipped it from Nashville. After insisting that it was very fragile and I had no faith in UPS or FedEx to safely transport it (the real reason was that I'd wanted to open it up and go through the contents, fondle the box, look through the books, and play the usb while I was there on vacation- I couldn't wait til I got home), she relented and let me slip it behind the last row of seats on the plane and then, since the plane wasn't full, let me change my seat to that row so I could sit in front of it.

When I arrived home, before even unpacking my luggage, I delicately cut through the mass of bubble and spread the treasures of the cabinet out on my living room floor to glory in it all.

|

| Full set of my photos of Volume 1 here |

|

| That ain't plywood, folks, it's solid oak |

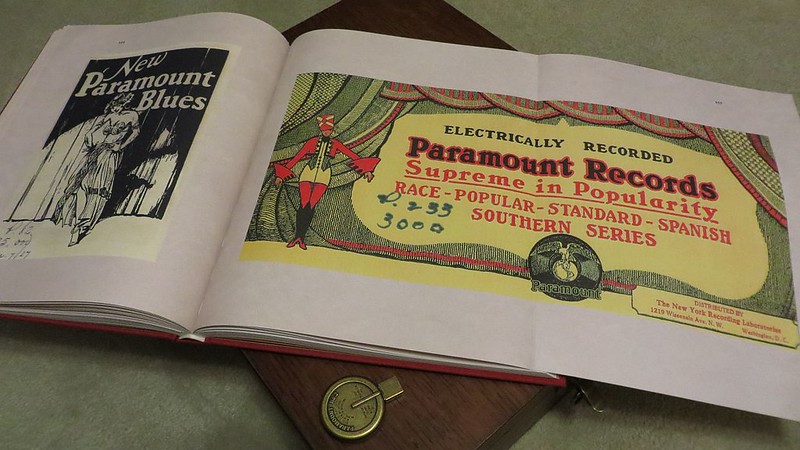

Volume two is just as physically gorgeous, updated to match the Art Deco period of its music, all aluminum, silver, midnight blue, and pink--

Jack has described the physical aspects of the sets as "witchcraft to lure you down the path to get you to the story" and that's very apropos, but he would have been more accurate to say stories, as the physical, textual, and audible elements of the sets tell a variety of tales-- Multiple intertwined histories of American music, American culture, Paramount the company, the stories of the musicians, some of which are more complete than others, and the tales within the songs themselves. I've had trouble getting this post written because I kept wanting to dive into some of those stories and digress all over the place. And heaven forbid I start talking about the music because with all the musicians represented in these sets I could go on and on and on. But there have been many articles written about Paramount and these sets (some of which I've included links to below) and maybe one of these days I'll get around to writing about the music and its effects on me. At the moment, I'm more interested in the perverse and contrary elements that abound in connection with these Cabinets of Wonder-- Contradictions having to do with Paramount, with Third Man and Revenant Records, and with myself.

The chief contradiction of Paramount was summed up by Jack at Yale when he said "What’s beautiful about [the company] is … the accidental capturing of American culture for the sake of a dollar". At both panel discussions, much was made of how Paramount didn't care who or what they recorded, didn't even care how the records were pressed-- Greil Marcus spoke of how they were so cheap that they mixed clay from the Milwaukee River that flowed below their factory into the shellac, making records literally from dirt. And Jack mentioned that, at nearly the same time Paramount was combing the country for musicians to record, archivists such as John Lomax, working for the Library of Congress, were doing the same but with a much more methodical and discriminating intent. But where those archivists did much to define the genres they collected examples of, Paramount did not. Their focus was not on what they were recording, but on who was going to buy those recordings and, subsequently, the expensively housed record players that were the company's primary product. The records and the music on them were almost an afterthought, created as an accessory to the record players, but an accessory that ended up selling in the hundreds of thousands of units, though never really making any money for the company.

But what happened to those records when Paramount closed in 1935? Amongst other things, there's the tale of angry employees going up to the roof of the factory and sailing masters of the records into the Milwaukee River, not even realizing that they were, essentially, setting that music on a course towards extinction. Those records could never be re-pressed and when the existing copies became scratched or broke or were just thrown away as technology advanced beyond 78rpms, that was it. As the years went by, Paramount's bounty went the way of the dinosaurs.

Fortunately, enough collectors held onto enough scratchy old copies of enough songs that, when Revenant and Third Man came along, they had a few thousand tunes to go through, which they culled down to one-thousand and six-hundred. That's eight-hundred songs per set. Seems like an overwhelming amount to sit down at your record player and listen to, doesn't it? And it's enough that, when people ask me about Volume 1, I'm hard-pressed to describe the diversity of the recordings included in it. And there are eight-hundred more coming on Volume 2. And yet these sixteen-hundred songs are just a fraction, a small fossil representation of the thousands that Paramount released in their 20 year existence. As Greil Marcus put it in the discussion at Yale, what we still have "is so rich and so great and so varied that I think you don't even think about what might be lost [because] you can't imagine that anything is better than what is left."

So along come Revenant and Third Man, pulling together what's left and giving us this glorious representation of what wasn't lost, and doing it with a mindset of "how would Paramount have done this if they gave a shit... and had the money?". The crux is that these sets ended up being too expensive for the masses. This music that was originally produced for a mass audience is now, despite the best of intentions, only available to those who have the money for it. Few people have been able to listen to the old 78s that existed over the years because the scarcity of those records has made them prohibitively expensive, up to tens of thousands of dollars for a single two-song record. And yet these Cabinets of Wonder, for all their value (fifty cents a song, if you do the math, plus the cabinets themselves and two chock-full books of information!), are still priced beyond the means of the average fan.

I can understand why they did it this way. Just sticking these songs on a handful of records and selling them in a series, or even just selling the two 800-tune flash drives by themselves, would pique a bit of interest, certainly. Third Man's project of reissuing the catalog of Document records, artist by artist, garnered some news and got fans talking. And I'm sure they've sold a fair number of the Document records. But to tell a story like Paramount's, to make the music and its history important, to make it desirable, you've got to present it in a special way. And yet, doing so ups the price and paradoxically limits the number of sets that will sell. It makes this music that was once of the masses more accessible than it's been for many decades, and yet still keeps it rarefied. This is frustrating to fans of Third Man Records, many of whom already scrimp just to afford $60 for a quarterly subscription to Jack White's Third Man Records Vault. Those fans just can't justify spending $400 for a bunch of old music, no matter how historic it is or how appealingly it's been presented. Should it have been done this way? Should Third Man and Revenant have created the gorgeous Cabinets of Wonder for people who want the full experience and then also sold the 800-song usb separately for those who want to experience the music but can't afford the whole shebang? Or would that just defeat the purpose of the full set? They've made it clear that, in contrast to Paramount's quest to make a buck, they're not making any money off of these sets. Jack stressed when Volume 1 was released that they priced them as cheaply as was possible and that they would have to sell the entire 5,000 run of sets created in order to just break even. Should they have done it differently and made the music more accessible and, in turn, made more money from it, the way Paramount did? I don't know. I do know, though, that I covet the hell out of my Volume 1 Cabinet of Wonder and all that it contains, and that I was practically drooling as I ogled the Volume 2 cabinet last week in Battell Chapel. If that sort of reaction was their intent then, yeah, they definitely did it right.

As for my own contradictions involving these sets and the panel discussion at Yale, there was a bit of a tussle between my inner fan-girl and my more rational side (they do that sometimes). The fan-girl, who unfailingly surges to the fore and tries to take over where Jack's concerned, wanted to sit there the whole evening and just stare at him, take in every detail of his face, his physique, the clothes he'd chosen to wear, how he listened to the songs played. I can do that when he's whirling around a stage, I can glue my eyes to him and forget that there's anyone else up there with him. But in this situation, just as at last year's event at the NYPL, I couldn't. My rational side won out for a change. I couldn't just sit and stare at him while the other speakers were talking, I couldn't be that rude when what they were saying was so very interesting, from Adia Victoria telling of the body of a lynched black boy being thrown into the lobby of a theater where Ethel Waters was performing, to Greil Marcus describing a scene from the film Ghostworld in which the character Enid first hears Skip James' Devil Got My Woman...

And when the music began... forget it. My eyes traveled up to the gorgeous ceiling of the nave behind and above where the panelists were sitting and then closed as the voices took me over and my head began moving in time with the rhythm of the piano and acoustic guitar. Something about the place made those sounds even more ghostly than they seem coming out of my record player at home, something about the way they floated around the rounded walls of the nave amplified their intensity. The sound coupled with the ideas and images all of the panelists were talking about made it impossible to focus solely on Jack. The fan-girl was perturbed by this, but I was in bliss. Rocking back and forth and waving the paper fan they'd given us on the way in to the chapel, I felt like I'd been transported to an old-time revival meeting and was being moved to motion by the spirit of the music.

Even more contrary and less rational was the financial aspect of this little road-trip. I've been whining to anyone who'll listen that I can't afford to order Volume 2 right now because I spent so much money travelling to shows on Jack's Lazaretto tour this summer, and yet I didn't hesitate to spend the equivalent of a Vol.2 to drive up to Connecticut and stay two nights just to hear a discussion of it. Perverse, huh? Yeah. But I've no regrets. The Cabinet will be available for a while and I'll just have to pine away until I can justify shelling out the money for it. What I felt in that sacred place that night, listening to the songs played and the ideas discussed in such a beautiful atmosphere, couldn't be bought in any store.

For those folks wanting to understand more, learn the history, and hear some of the music, the magics of the interwebs come to your rescue-- Here are both panel discussions in their entirety:

And a couple of good articles about the historical aspects of Paramount Records:

- Paramount Records: The Label Inadvertently Crucial To The Blues

- The Story of Paramount Records – Black History Month in Wisconsin

- Why Nerdy White Guys Who Love the Blues Are Obsessed With a Wisconsin Chair Factory

- Revisiting The Grandaddy Of Record Labels, Paramount Records

I hope you get sucked in like I did.