|

| A couple of photos I snuck when the museum guard's back was turned. For more views, go here. |

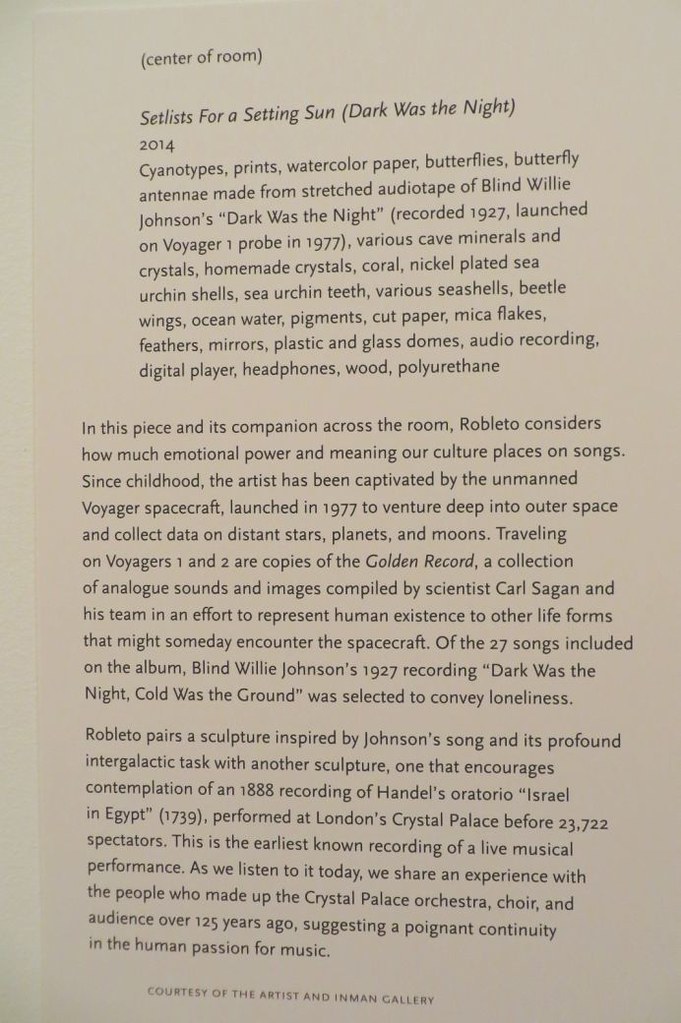

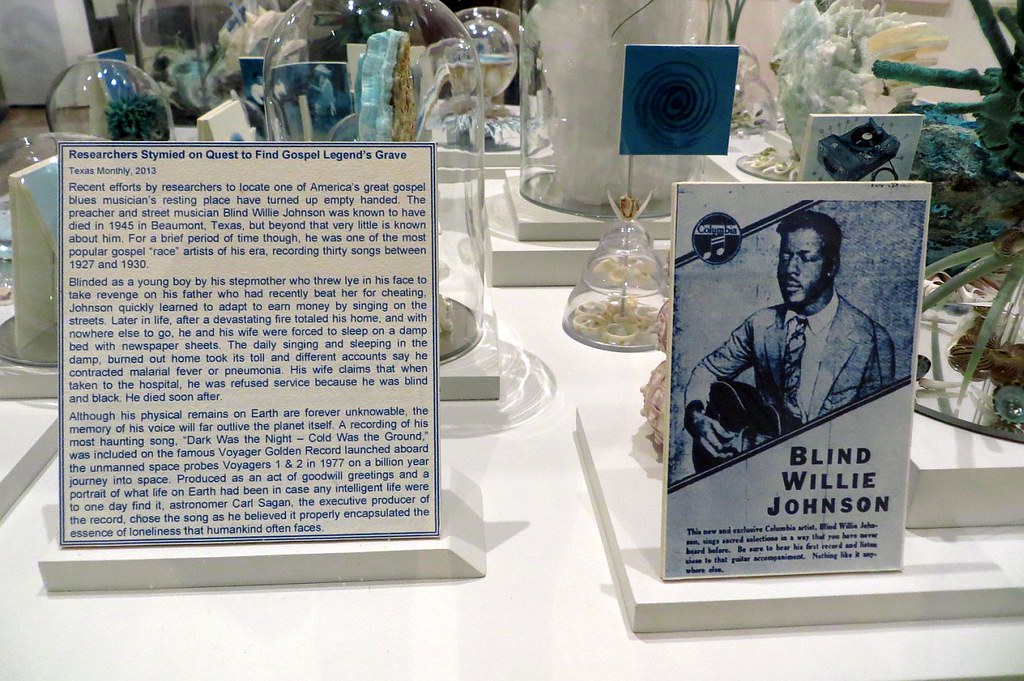

On the other side of the room, another Setlist for a Setting Sun, this time Dark Was the Night. Still blue and white, with more crystals, shells, and iridescent wings under glass, but this time with rockets taking off for the dark expanses of space. A Voyager in search of other voyagers, carrying the sounds of a man who could only see darkness. We've kept track of Voyager all these years, but have no idea where Willie Johnson, whose spectral humming and eerie bottleneck are an angel's song of a different sort, ended up.

|

| Again, my own surreptitious photos. More from the artist's site here. |

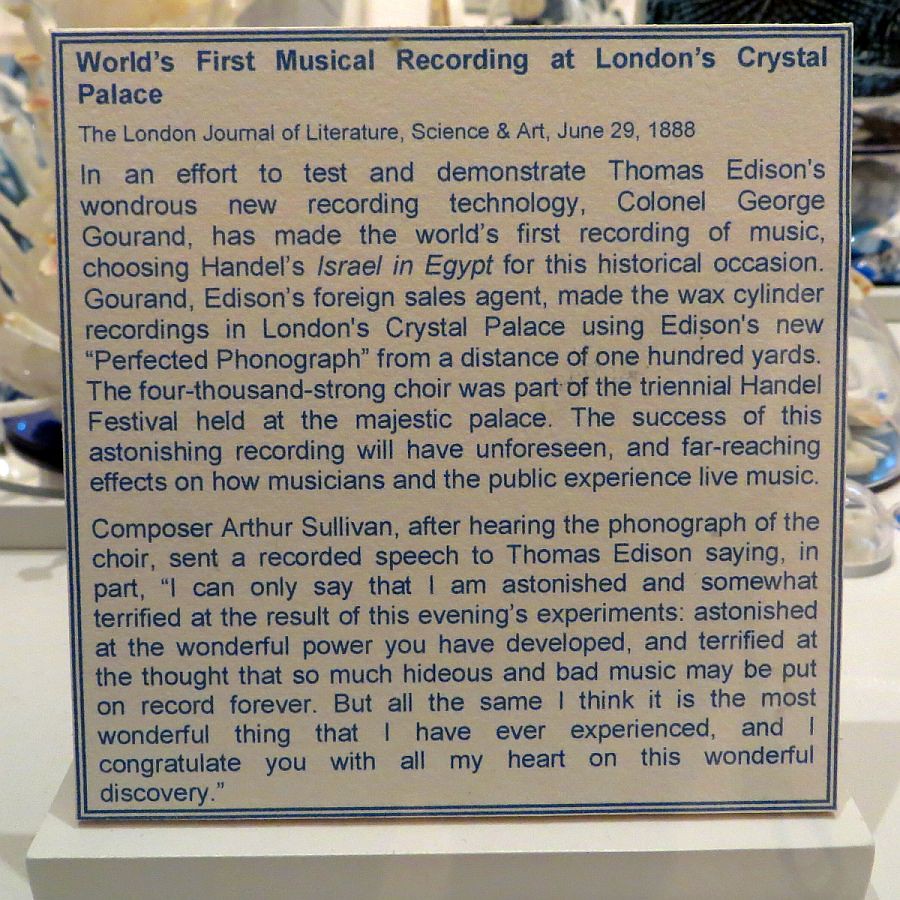

It's always exciting to me when I run into things that are meaningful to me presented in entirely knew contexts. Dario Robleto's current exhibit at the Baltimore Museum of Art is a perfect example and I got a bit giddy when the pieces came together. At a distance, it's just an assortment of shells and glass and bits of stuff inside a pair of plexiglass cubes and I almost walked past without taking the time to catch the connections. Fortunately, I stopped long enough to read the little card about the Edison phonograph recording of Handel's oratorio at the London Crystal Palace. You see, it wasn't too many months ago that I read a book called Perfecting Sound Forever, by Greg Milner, which begins with accounts of several of Thomas Edison's "tone tests" such as took place at the Crystal Palace. So to read that card, then to pop on the headphones hanging next to the exhibit and hear what that London audience heard was fairly amazing. It was a digital copy I was listening to, yes, but still, the effect it must've had on those people, people who were hearing for the very first time an early, unsophisticated version of the recorded sound that we take for granted, was so easy to imagine.

And then I stepped across the room and put on a second pair of headphones and heard Blind Willie Johnson's Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground, a song I first heard a couple of years ago, early on in my exploration of blues music, and one that immediately defined the blues for me. And here it was, this primal, innately human sound, linked with man's attempts to communicate with alien species.

What was the one thing that tied all of these elements together and made them significant to me? If you've read more than a few entries here, I'm sure you can guess. Yup, that's right, it all comes back to Jack White. The musician who was my gateway to blues music, without whom I'd never have heard of Blind Willie Johnson or known that Johnson's song was chosen by Carl Sagan for inclusion on Voyager's Golden Record (I'd learned about this originally in the companion book to Martin Scorsese's PBS series, The Blues, and it coincidentally came up again recently in an interview that Dan Rather conducted with Jack). Whose songs have inspired a craving in me to learn how music is made and whose mention of Milner's book led me to pick up a copy and learn about the effect of those early phonograph recordings on concert-hall audiences. Is this meaningful synchronicity or the delusions of apophenia? I know it seems maddeningly myopic but, from my perspective, it's just the opposite-- The things I've been exposed to through Jack have opened up a whole world for me and broadened my appreciation of so many forms of music and art and even science. If not for my obsession with him, I would have walked right past those plexiglass cubes at the BMA and thought, "Shells and shit under glass. Pretty, but how is this really art?" I would have missed the connections that made me stop long enough to understand the message of Dario Robleto's art. The message itself wouldn't have meant as much to me.

And Robleto's message is important. The need to communicate is one of mankind's earliest and most primary. We've been using art and music as means of communication since we could speak, if not even earlier. And we're using music now to try to communicate with species beyond our own world. Art such as Robleto's reminds us of this, makes us understand how music can bring us together and connect us, and how vital it is to not take the need or the method for granted. Words are great for getting a point across, but music can communicate feelings so much more succinctly.

Excellent review of the exhibit from Baltimore's City Paper, here.

No comments:

Post a Comment